MEITY on 29th June 2020 blocked 59 apps using Section 69A of the Information Technology Act coupled with the Blocking Rules of 2009. (Procedure and Safeguards for Blocking of Access of Information by Public). Among the blocked apps were apps like Tik Tok, UC Browser and Cam scanner which are widely popular in the Indian market. The reason stated for blocking these apps were that these apps threatened the sovereignty and integrity of India, defense of the state, security of the state and public order. Section 69A of the Information Technology Act, 2000 provides for blocking of public access of these apps for the above reasons. The press release further states that ‘emergency measures’ had to be used as these apps were said to be engaged in data mining and profiling which compromised the privacy of Indians as well as posed a threat to the sovereignty and security of India. Interestingly, this move comes a couple of weeks after the popular file sharing app ‘We Transfer’ was blocked in India. SFLC.in had filed a RTI request with the Dept. of Telecommunication to request for the order of the block but hasn’t received a response yet.

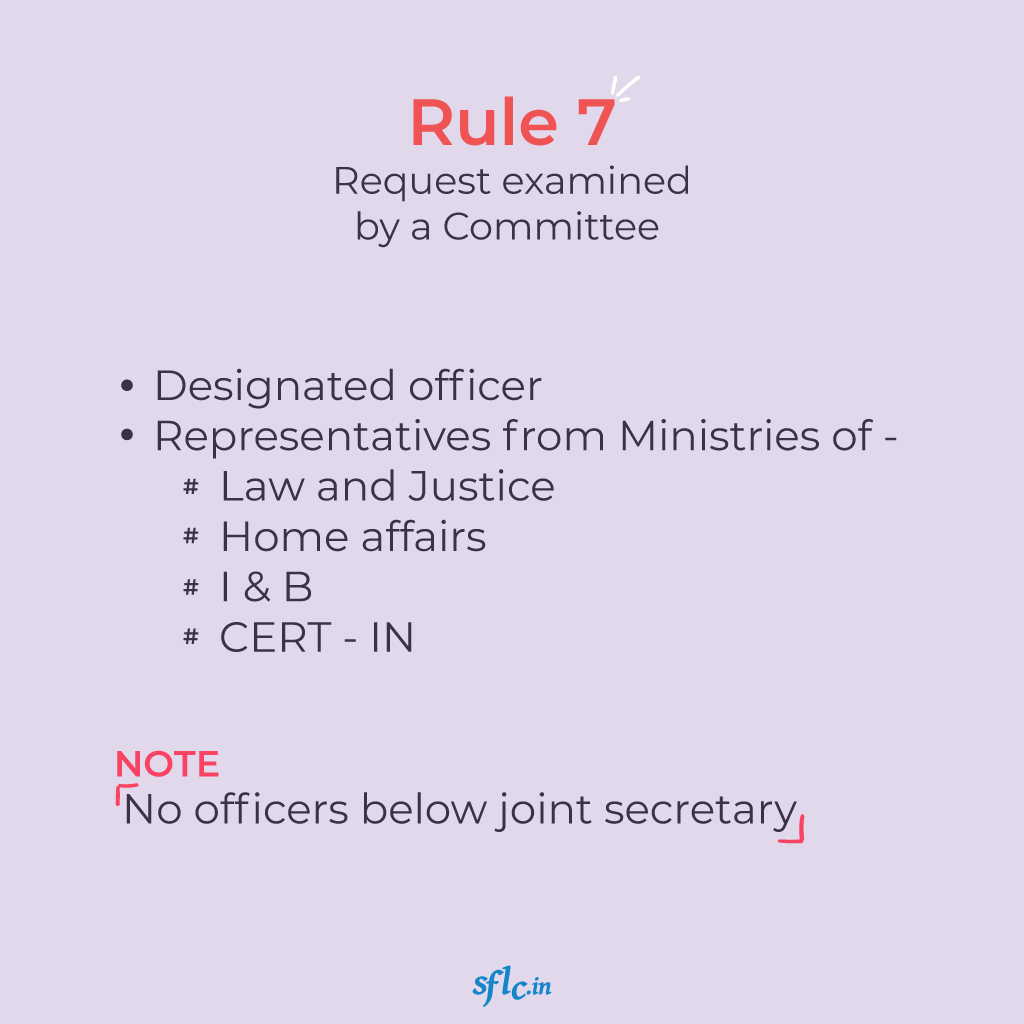

The press release further states that the Indian Cyber Coordination Center had also recommended blocking these apps. CERT-In as well as MEITY had also received several representations from citizens which brought up concerns about the use of these apps. The press release also mentions about the credible inputs that have been received highlighting how these apps harm the sovereignty and integrity of India. According to the press release, the said move is aimed at protecting the integrity and sovereignty of the country.

The press release nowhere mentions that these apps are of Chinese origin thus not providing attribution.

On 27th July 2020, an additional 47 apps were blocked, these apps were said to be the lite versions of the previously blocked apps. There has been no press release for these additional apps or any order. SFLC.in has filed a RTI to get the order.

Law relating to website blocking

Website blocking is done using Section 69A of the Information Technology Act, 2000 coupled with The Information Technology (Procedure and Safeguards for Blocking of Access of Information by Public) Rules, 2009 hereafter referred to as the ‘Blocking Rules, 2009’.

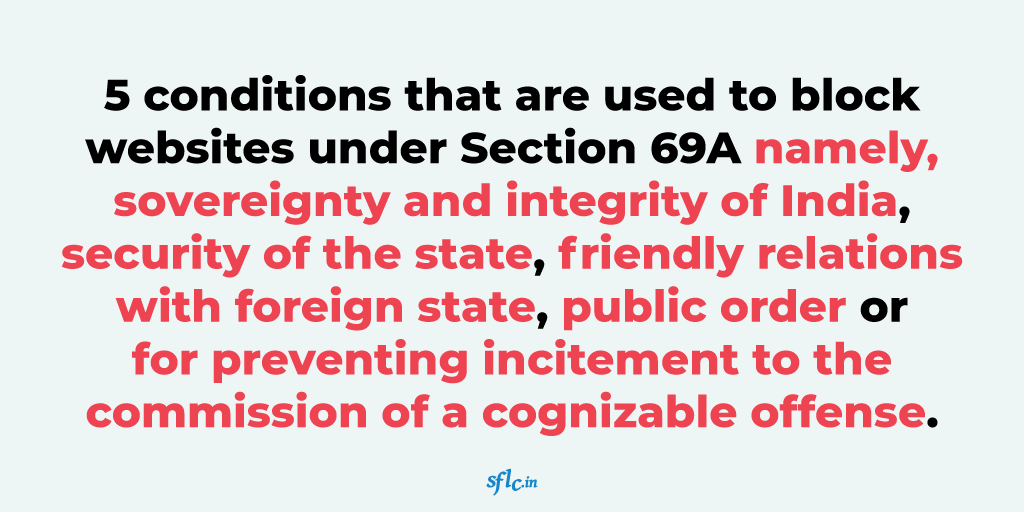

Deconstructing Section 69A - The section says that under 5 conditions namely, in the interest of sovereignty and integrity of India, the security of the state, friendly relations with foreign state, public order or for preventing incitement to the commission of a cognizable offense, any agency of the government of any intermediary can be asked to block the access of information for the public. The order has to be in writing and has to be done according to the procedure as well as safeguards prescribed in the Blocking Rules.

In case an intermediary doesn’t comply with this, they will be liable to pay fines as well as face imprisonment for a period of up to 7 years.

An Intermediary as defined by the Section 2(w) of the IT act would include telecom service providers, network service providers, internet service providers, web hosting service providers, search engines, online payment sites, online auction sites, online market places, cyber cafes etc,

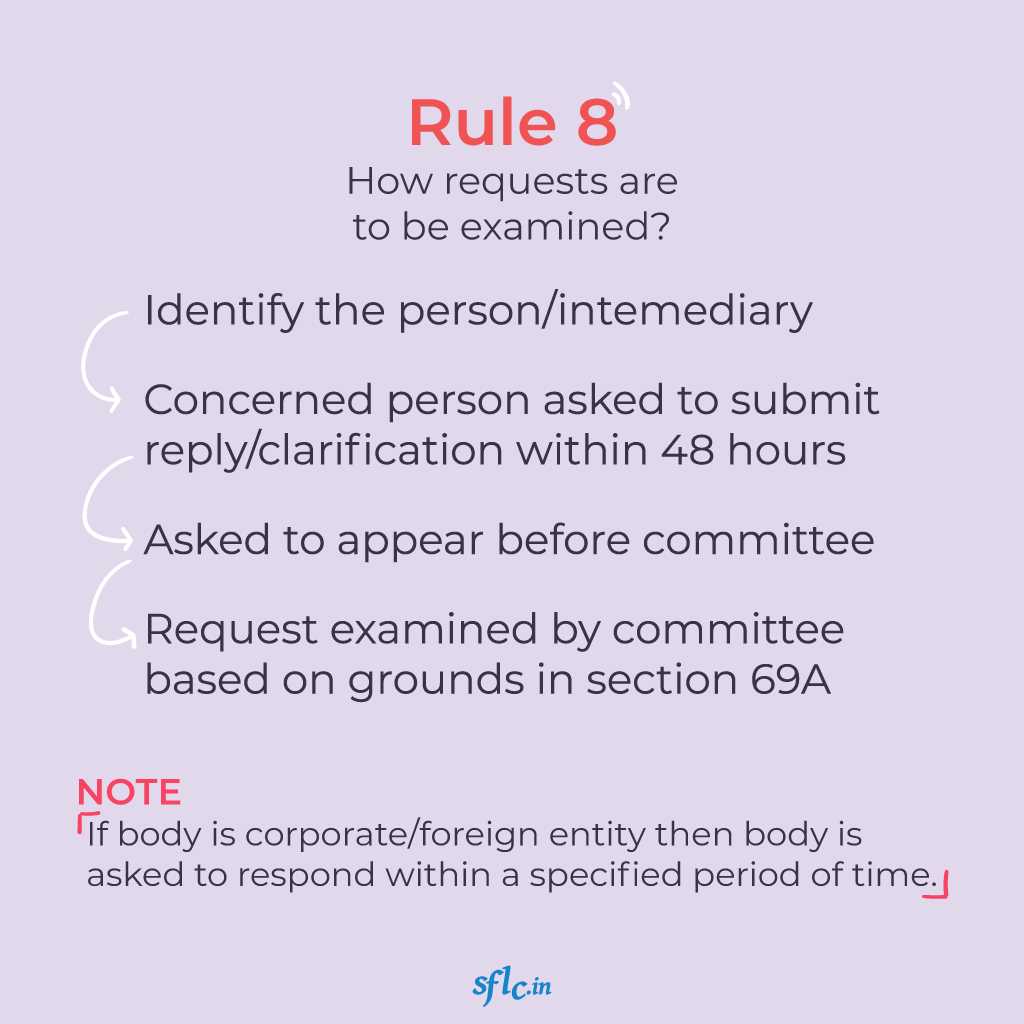

The Blocking Rules, 2009

The Blocking Rules gain their powers from clause (z) of sub section (2) of section 89 of the IT Act and are read in conjunction with Section 69A of the IT act.

In Shreya Singhal V. Union of India, The Supreme court said that Section 69A of the IT act is unlike Section 66A of the IT act and is not narrowly tailored. The court said that ‘ First and foremost, blocking can only be resorted to where the Central Government is satisfied that it is necessary so to do. Secondly, such necessity is relatable only to some of the subjects set out in Article 19(2). Thirdly, reasons have to be recorded in writing in such blocking order so that they may be assailed in a writ petition Under Article 226 of the Constitution’

The court upon the constitutionality of the Blocking rules, 2009 ruled that they weren’t ‘constitutionally infirm’ in any way. The court had also said in the judgment that blocking of websites only takes place with a reasoned order after complying with multiple procedural safeguards. It can be read that the opportunity of hearing is provided to the content originator thus making the rules constitutionally sound. The orders of blocking can also be challenged in courts as inferred from Shreya Singhal judgment.

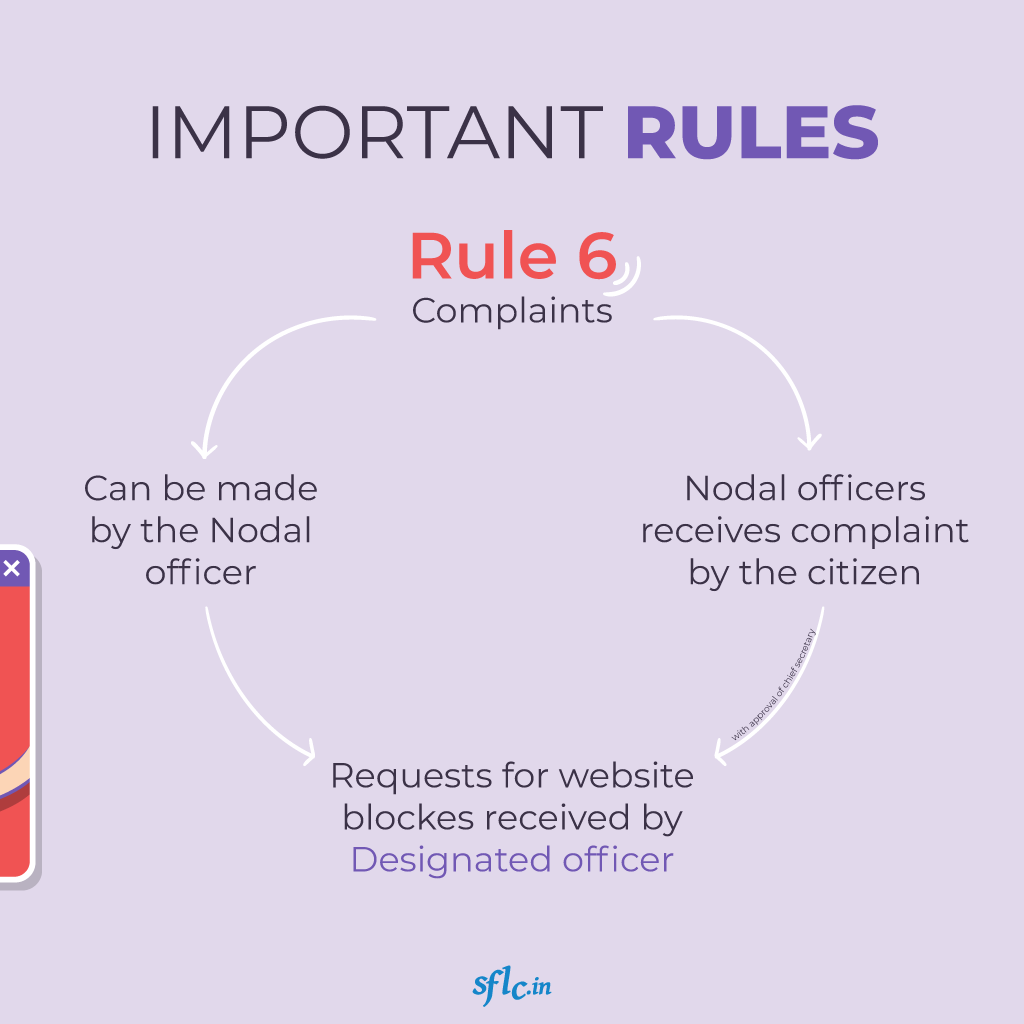

How will this take place?

A number of these apps like Share It, UC Browser come pre installed on devices. We think that the pre-installed and the already installed apps will continue to function as long as they don’t require any live feed to function.

In brief, when apps and websites are blocked, the domain name and host names are asked to be blocked by the Internet Service Providers (ISP’s). Play store(Google) and App store(Apple) are also asked to take down the apps. ISP’s will be asked to block each domain name and host name which can be rather difficult to achieve and sometimes lead to over blocking.

A paper written by Gurshabad Grover, Kushagra Sinha and Varun Bansal explains the technicalities of website blocking. The paper can be accessed here.

Our Take

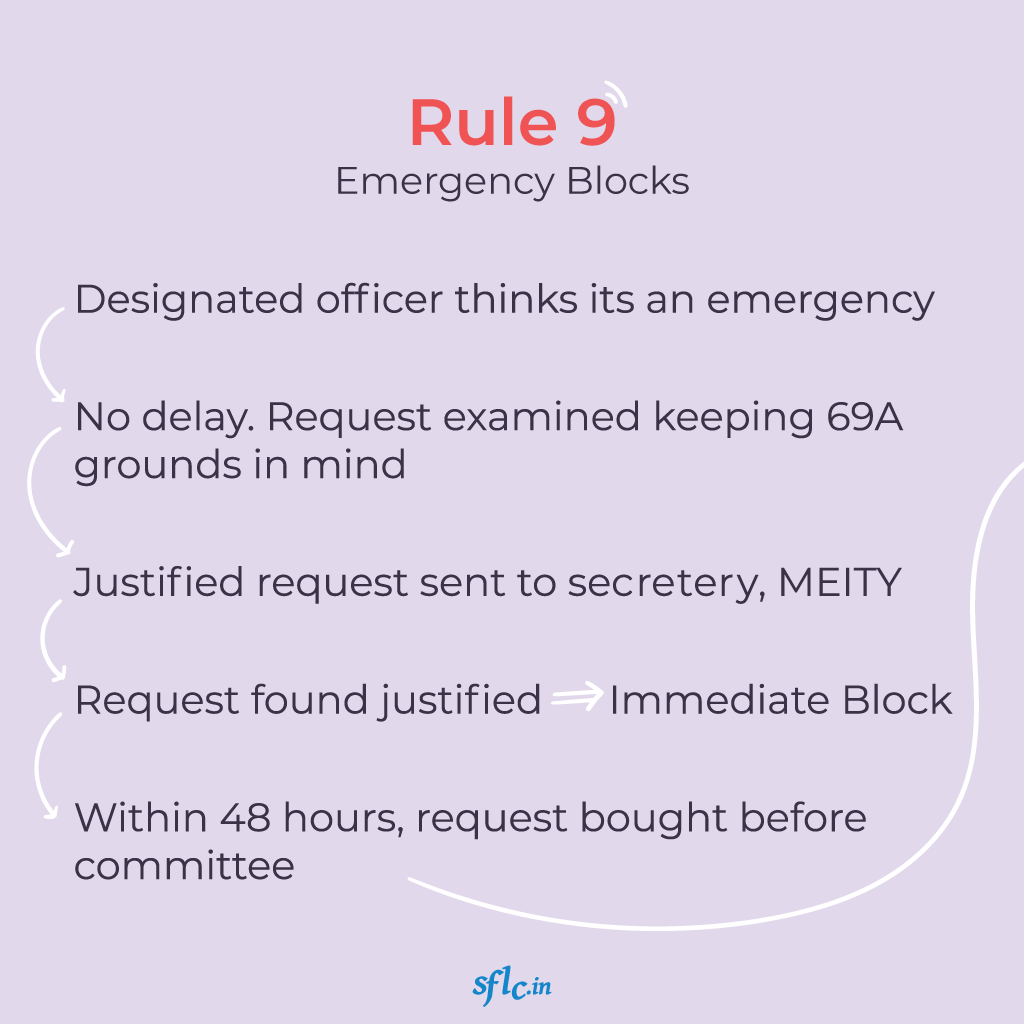

To the best of our understanding, the 59 apps that were blocked on 29th June, 2020 were blocked using the emergency provision stated in Rule 9 of the Blocking Rules. According to the statement released by ByteDance (Tik Tok’s parent company), they have been invited by the Government officials for consultation. Media reports suggest that the ban imposed is an interim measureunder Rule 9 of the Blocking Rules. We also hope that all 59 apps companies are given due hearing. The additional 47 apps also seem to have been blocked similarly.

We have also filed a Right to Information request asking MEITY for certain clarifications regarding the procedure followed to block these apps.

This is the first time, that we have seen a press release in case of the first 59 appms which informs the public of the banned apps, we appreciate the government’s efforts in providing timely information as well as request for greater transparency in the future. Unfortunately, the legal order banning these 59 apps is not available in public domain. The availability of the order can help with transparency and in ascertaining if the due process has been followed. There is no order or press release by the Government available in the public domain in case of the latter 47 apps.

In absence of a Data Protection law, India has been facing trouble with establishing rights of data fiduciary as well as the recourse available in event of unauthorized sharing of data. Similarly in absence of a cyber security policy and data localization requirements, India can find itself at loss in case where foreign entities share data of its citizens.

We also would like to understand how the specific these apps were picked among others.

We have filed RTI’s earlier with MEITY to understand and keep track of the instances of website blocking that have been happening in India. The resources can be accessed here.

The confidentiality clause as per Rule 16 of the Blocking Rules is problematic as transparency in the case of such blocking orders should be the norm.

The interests of the country is supreme and the Government can take decisions to protect this interest, However, as a democracy governed by the Rule of Law, we should hold ourselves to much higher standards when compared to countries like China and should follow the procedures laid down by law while issuing blocking orders.