SFLC.in files a Representation Regarding Mandate to Provide Aadhaar Details to Approach the GAC

The Ministry of Electronics and Information Technology (‘The Ministry/MEITY’), on January 27, 2023, notified three Grievance Appellate Committees[1] (‘GAC/s’), which shall be the forum for users to appeal decisions issued by Grievance Officers of intermediaries. In order to access this appellate forum, however, users are required to furnish their Aadhaar Number, and their name as it appears on their Aadhaar Card. This mandate contradicts the verdict of the Supreme Court of India in Justice K.S. Puttaswamy (Retd.) v Union of India[2], and unduly creates an obstacle in the exercise of a statutory right.

Grievance Appellate Committee

The provision for these Committees was created through an amendment to the Information Technology (Intermediary Guidelines and Digital Media Ethics Code) Rules in October, 2022[3] (hereinafter, ‘IT Rules’). Apart from increasing the due diligence requirements of intermediaries, and a requirement for intermediaries to respect the rights of citizens under Articles 14, 19, and 21 of the Constitution of India, the Amendment also enables the Central Government to establish Grievance Appellate Committees.

According to the Rules, each such Committee shall comprise of three members (including a chairperson), appointed by the Central Government. Two out of three of these members shall be independent. Rule 3A(5) allows the Committee to invite the assistance of a person with the requisite qualification, experience, and expertise in the subject matter.

The Committee, which shall operate entirely digitally, shall be the appellate body which a user can approach, in case they are dissatisfied with a decision taken by the Grievance Officer of a social media intermediary. In other words, for example, if person ‘A’ is aggrieved by the takedown of content they had posted online, they would first raise their grievance with the Grievance Officer of the intermediary. Assuming that said Officer upholds the takedown decision, A may appeal against this decision before the GAC. As per the Rules, the intermediary would have to comply with the decision of the GAC. [4]

The Mandatory Requirement: Aadhar

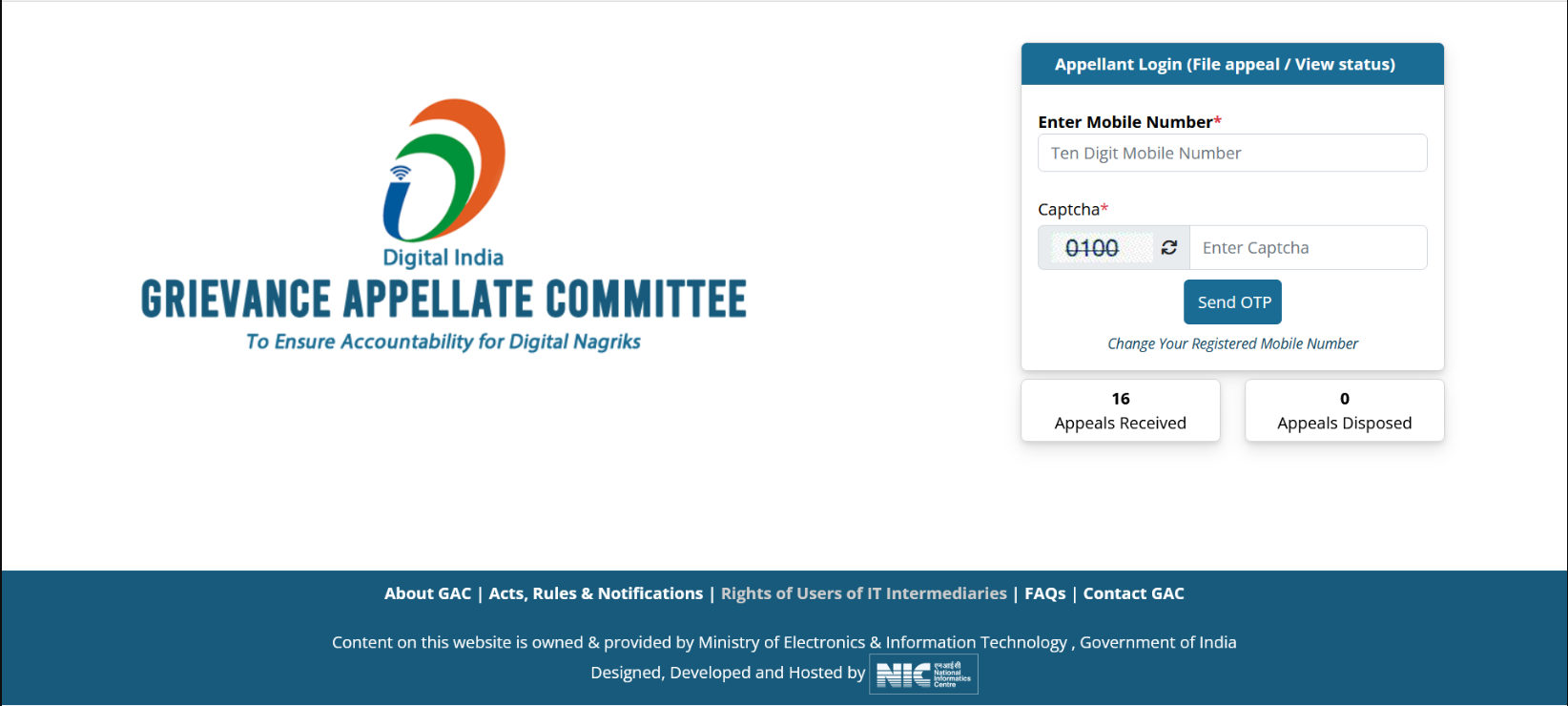

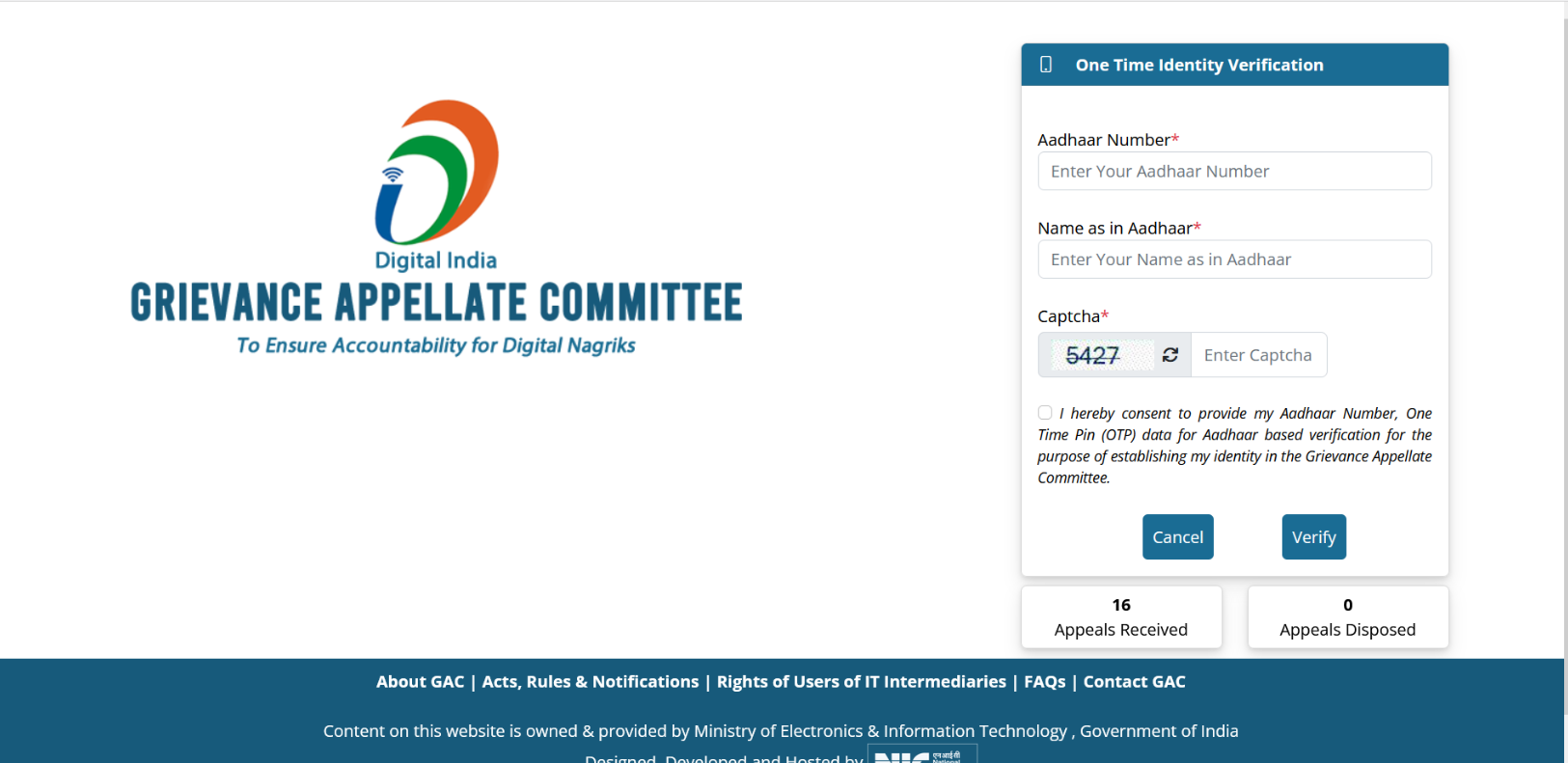

As a digital adjudicatory entity, the Appellate Committees are only accessible through their website[5]. The first step to filing an appeal is an ‘Appellant Login’ verification window, in which the appellant/prospective appellant will verify their mobile number through a One-Time Password (OTP) sent to them. After crossing this login stage, the user is redirected to the ‘One-Time Identity Verification’ page, on which they are required to provide their Aadhaar Number, and their name as it appears on the Aadhaar Card.

As can be seen above, there is no option available for a user to opt for an alternative identity verification process (such as by sharing their Passport, voter ID, or any other form of State-issued identification). Instead, the user is required to consent to providing their Aadhaar Number “for the purpose of establishing (their) identity in the Grievance Appellate Committee”.

Effectively, this makes it mandatory for any user who wants to file an appeal to-

(a) possess an Aadhaar Number, and

(b) to share that Aadhaar number with the Grievance Appellate Committee.

The Issue

This mandate to possess and provide an Aadhaar Card is problematic on several fronts.

Firstly, concerns about the widespread use of Aadhaar as a mandatory proof of identification had triggered a series of interim orders from the Supreme Court during the adjudication of the Justice K.S. Puttaswamy (Retd.) v Union of India litigation, and finally resulted in the verdict of the Court which restricted the use of Aadhaar by the Government.

The Supreme Court did this through a two pronged approach: first, it stated that the mandated use of Aadhaar should only be for those benefits, schemes and services of the Government of India which were aimed to aid a certain deprived class who are unable to receive said benefits, schemes, and services. Therefore, effectively Aadhaar cannot be used as a compulsory instrument of identification for all government services. Secondly, it emphatically stated that the “net of Aadhaar” should not be widened unduly by expanding the scope of the benefits, schemes and services offered by the Government of India. Therefore, it limited the expansion of Government services for which the use of Aadhaar can be made mandatory[6].

Viewed in this light, the compulsion to provide Aadhaar details on the GAC’s website contradicts the principles of the Puttaswamy judgement, and raises serious questions about its legality.

The second concern stems from the restriction to exercise a statutory right which arises from the compulsion to furnish Aadhaar. The GAC was introduced by the Ministry in order to allow users to press their right of freedom of speech and expression, which they feel have not been appropriately protected by private intermediaries, into service. This statutory right to approach the GAC, created by virtue of Rule 3A(3)[7], is hampered when only those users who possess an Aadhaar are ‘eligible’ to file an appeal. Such a compulsion, the Supreme Court has ruled, would not pass the muster of the proportionality test as laid down in the Puttaswamy judgement[8].

Thirdly, the portal does not allow for any alternative means of verifying the users’ identity. Alternative State-issued identifications can achieve the same objective (of establishing the users’ identity). Disallowing the use of Aadhaar where alternative “IDs” can achieve the same objective qualifies as a coercive step and must be reconsidered urgently, keeping in mind the principle in Puttaswamy which resists the ubiquitous use of Aadhaar in India.

Conclusion

As laid out above, mandating the production of Aadhaar is a coercive step, especially since accessing a statutory right has been made contingent on it. There is no law which legitimizes such a use of Aadhaar, nor is there a rational nexus or necessity - the objective of identifying an appellant can be established through alternative IDs; and there is no reasonableness in limiting such ID to Aadhar. Furthermore, no argument for public interest can be made to satisfy the restriction of access to a statutory right which is created through the current GAC mechanism for verifying identification. The failure of the proportionality of this measure is apparent prima facie, and as such, an immediate rectification is in order.

Raising these concerns, SFLC.in filed a representation with MEITY on March 2, 2023 (available below), and forwarded the recommendation to allow alternative identification documents to allow all users to exercise their statutory right.

[1] https://www.meity.gov.in/writereaddata/files/243258.pdf

[2] (2019) 1 SCC 1

[3] https://egazette.nic.in/WriteReadData/2022/239919.pdf

[4] Rule 3A(7) Every order passed by the Grievance Appellate Committee shall be complied with by the

intermediary concerned and a report to that effect shall be uploaded on its website.

[6] Supra Note 2, Paragraphs 511.13, 511.13.1

[7] Rule 3A(3) Any person aggrieved by a decision of the Grievance Officer may prefer an appeal to the

Grievance Appellate Committee within a period of thirty days from the date of receipt of

communication from the Grievance Officer.

[8] In Noel Harper v Union of India 2022 SCC OnLine SC 434, the Supreme Court held that the mandatory requirement under the amended Foreign Contribution (Regulation) Act, 2010 on office bearers of registered organisations to mandatorily disclose their Aadhaar Number as an identification document for the grant of certification fails the test of proportionality laid down in Puttaswamy.